|

| Federal soldier reads near former slave market (George Barnard/LOC) |

Over the course of time, I have driven

or walked most of the surviving thoroughfares that ran through wartime

Atlanta -- a young city with so much promise, yet destined to endure so much

devastation.

Those avenues weren’t paved in 1864. Peachtree, Whitehall and Alabama, for

instance, came in only two choices: Dusty or muddy.

I have witnessed

downtown’s many ups and downs over the nearly 30 years in which I have worked

for two employers. Hotels, conventions, concerts, sporting events and museums bring

throngs of people to the area. But people also walk among panhandlers and pass

many commercial and retail establishments no longer in their heyday.

Still, there is always the promise of a new day, as touted by the city’s

emblem, a rising phoenix and the words “Resurgens,” or resurgence. Georgia

State University, which has expanded its campus footprint in recent years, is

an example of regeneration in the core district.

The Atlanta

of the Civil War was a boom town, just beginning to acquire the muscles and

mettle that one day would make it the behemoth of the South. In 1860, on the

war’s eve, it had fewer than 10,000 residents, making it the fourth largest

city in Georgia, behind Savannah, Augusta and Columbus.

|

| Scott Peacocke, Charlie Crawford, Mary Elizabeth-Ellard |

Residents of

nearby Decatur thought the people of Atlanta, largely made up of laborers and

carpenters, to be uncouth, said Mary-Elizabeth

Ellard, a board member of the Georgia Battlefields Association. Prostitution was the 10th most common occupation.

While the war effort led to a doubling of the city’s population,

it was not uncommon to see chickens pecking and cows grazing between homes. The

“suburbs” weren’t that far away from the transportation, manufacturing and

supply center that had been under martial law since May 1862.

With it nexus

of four railroad lines, Atlanta quickly showed its importance to the

Confederacy and Federal forces who finally reached its outer fortifications in

July 1864.

This past Sunday,

two days before the 150th anniversary of the Battle of Atlanta,

which raged only a couple miles to the east, I participated in a downtown Atlanta tour led

by Ellard and Charlie Crawford of the GBA. Joining us was Scott Peacocke, a

friend and former colleague at The Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Even with umbrellas, we became nearly soaked as rain poured down during the second half of our walk. No matter, we were in our element.

|

| Click GBA map to see wartime, modern features downtown |

Peacocke and

other AJC staffers have just wrapped up a superb sesquicentennial online

project, “War in Our Backyards,” in

conjunction with the Atlanta History Center.

As the detailed

presentation points out, 40 percent of the city was in ruins when Sherman began

his March to the Sea. But don’t lay all the blame solely at his feet.

“It started when Confederate military planners stripped

and leveled buildings and homes on the city’s outskirts to build the extensive

fortifications that Sherman found impenetrable. During the summer siege, Union

artillery fire hit many of the city’s major structures, setting many afire.

Miles of trenches dug by both sides scarred fields and roads. When the

Confederates made their retreat, they blew up their ammunition train, damaging

scores of homes, and burned the massive Atlanta Machine Works factory,” the AJC

said.

Looters, arsonists and the need for material for Union

forts took their toll until November 1864, when Sherman “ordered the

destruction and burning of all facilities with potential military value,

including ripping up rail lines and destroying Atlanta’s transportation

infrastructure.” He also ordered out the remaining civil population, who were

offered a one-way train ride either north or south.

|

| Crawford near site of Episcopal church that was shelled in 1864. |

Virtually

nothing from wartime downtown Atlanta remains today and only a guided tour and

some imagination can provide an adequate picture. I was very impressed by the

GBA’s expertise and materials compiled by Crawford.

Our walk was

aided by images taken by George Barnard,

a contract photographer for the Federal army who arrived after the city fell on

Sept. 2, 1864. The remainder of this blog post contains many Barnard photos and

current views -- though some of those views can only be approximated because of

buildings and the construction of bridges and viaducts that in effect changed

the elevation of much of downtown. All of the Barnard photos here are in the Library of Congress collection.

We began our tour near the picturesque Candler Building, where a Confederate commissary once sat, and proceeded to Ellis and what was then Ivy, where the first Union siege shell landed on the afternoon of July 20, 1864. It was a 20-pound Parrott round fired by DeGress' Battery a couple miles away. A false story began in 1888 saying a little girl and her dog were killed, said Crawford. It is true that between 20 and 25 civilians died over the coming weeks from shelling, with about 100 injured. "As more shells fell, more people got the message." The fear of falling shells was accompanied soon by gnawing hunger as food supplies became increasingly scarce.

|

George Barnard took this panorama view (click to enlarge) from the Female Institute. In his image, the Medical College is to the far left. The home of John Boutell stood where the Budget car rental building is now. Boutell was a building designer and carpenter. We proceeded to the Calico House, which resembled fabric of that name. Near Grady Memorial Hospital stood Peck & Day, which made thousands of Joe Brown Pikes, named for the Georgia governor who ordered the manufacture of these impractical homeland defense weapons. The state government's Sloppy Floyd Building is located where Spiller & Burr made finely crafted pistols and revolvers for the Confederate government. They could not, however, be mass produced. Getting items to the front lines also was a major problem for the Southern war effort.

The passenger station served several rail lines and was a vital part of the city. After Atlanta fell on Sept. 2, it was used, too, by Federal forces before its destruction. The view above is looking northwest from Calhoun Street (Piedmont Avenue).

Most Federal troops camped outside downtown Atlanta after its fall, but a few regiments were based there. Above, tents of the 2nd Massachusetts fill the back lawn of Atlanta City Hall. Milledgeville was Georgia's capital during the Civil War. Eventually, City Hall was moved and the state Capitol was constructed on the site during the 1880s. (The current Capitol view was taken during a previous tour).

Our by-now drenched group made its way to Whitehall Street, which was lined with all kinds of businesses and offices vital to the Confederacy. Barnard's view at top is looking east along Alabama Street. Atlanta National Bank is the small white building and the Georgia Railroad Roundhouse is in the distance.

According to an Atlanta Preservation Center exhibit, Barnard's task was not easy. "He and his staff traveled dirt streets and rough roads in a covered wagon -- carrying equipment, chemicals, and, critically, chemicals ... that were made of glass."

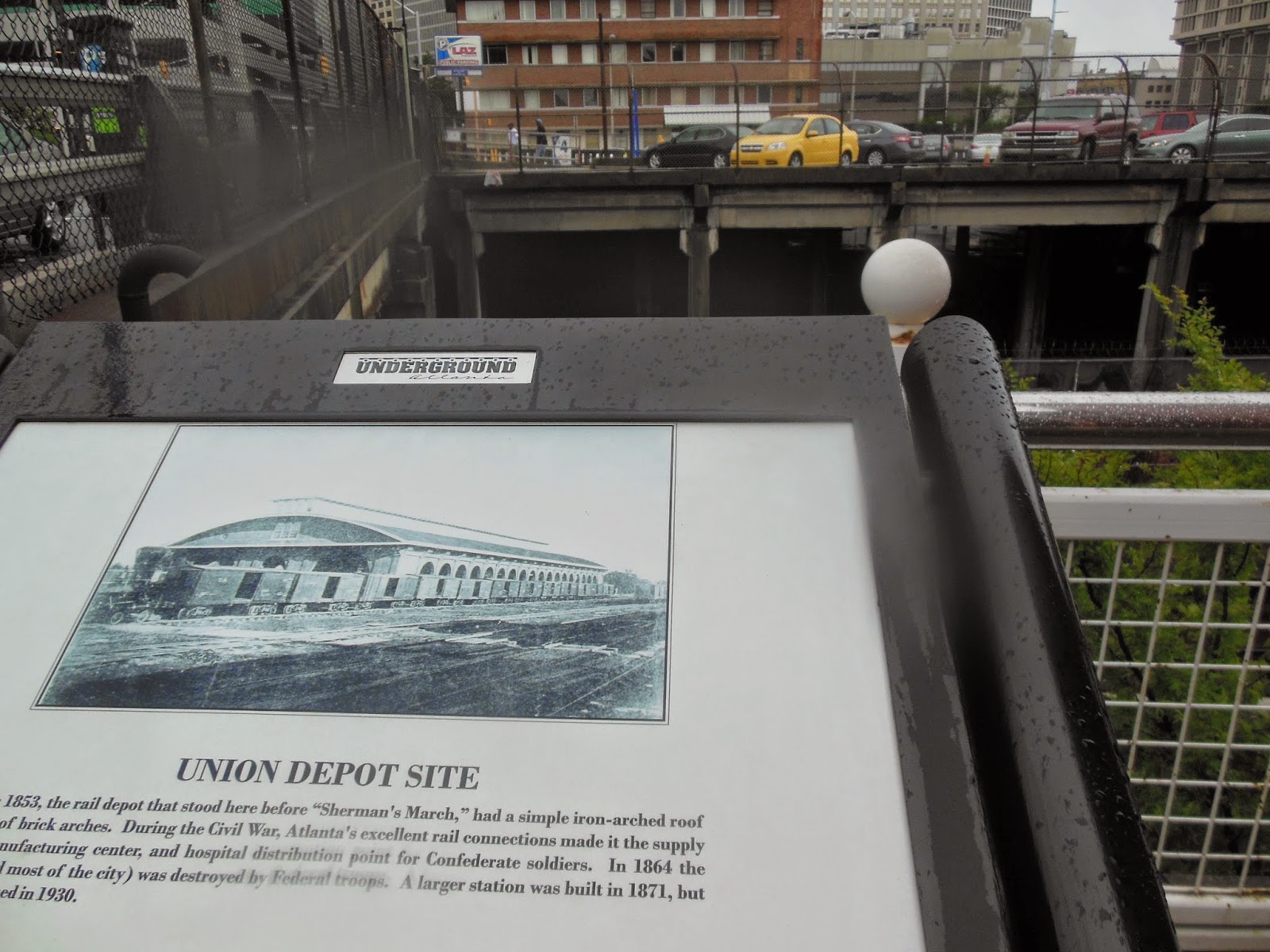

Sherman wanted to be sure Atlanta lost its war-making capabilities. The destroyed car shed (top) is shown in November 1864. Union troops used large iron bolts to bring the foundation down before setting fire to the remains. This was a devastating loss for Atlanta.

The 111th Pennsylvania camped in front of Trout House and Masonic Hall. The Trout House was a hotel and meeting place before and during the Civil War. It was destroyed. Georgia State University now covers much of this part of downtown.

After a couple more stops, we concluded the tour back near the Candler Building.

I asked

Crawford, president of the GBA, why he conducts so many tours in North Georgia

and metro Atlanta.

“You don’t

get to preserve land unless people think you should preserve land,” Crawford replied.

The tours raise awareness and educate the public about a site’s importance for the future, he said.

The tours raise awareness and educate the public about a site’s importance for the future, he said.

Excellent tour. Wish I could have joined you. Just finished reading "The Bonfire," by Marc Wortman, which was about the siege and burning of Atlanta. I'm sure you have read it.

ReplyDeleteThat is on my rather long list, Dean. But I plan to get to it.

ReplyDeletehttp://atlantahistorycenter.tumblr.com/post/40029658596/this-george-n-barnard-photo-of-the-thomas-frazer

ReplyDeleteThis comment has been removed by a blog administrator.

ReplyDeleteThis is so interesting. Thanks, Phil.

ReplyDelete